The Spanish plural morpheme system may in fact present phonology and statistics that lead to greater ease of acquisition of the noun morphology. First, in Spanish, the two plural allomorphs /-s/ and /-es/ form simple codas. The dominant /-s/ plural is typically added to the singular form of the words (e.g. taza-s 'cup-s'); /-es/ is only added to nouns ending in consonants and stressed vowels (e.g. reloj-es 'clock-s'). Sixteen two-syllable novel words, eight feminine (-a ending) and eight masculine (-o ending), were created. This control also allowed us to test children's ability to generalize their grammatical number knowledge to novel words. The syllables used were highly frequent in written Spanish by children (Justicia, Santiago, Palma, Huertas & Gutiérrez, 1996).

The plurals form simple codas ending in -as for feminine and -os for masculine. This manipulation meant that in all cases, the plural sound in the determiners was always a voiceless regardless of being presented before a voiceless or voiced consonant. Finally, the present results are suggestive, but do not conclusively indicate, that children might use plural morphosyntax to bootstrap learning of new words.

Children in our study correctly directed attention during the plural cue trials; however, it is not clear if they were learning the novel object names. Jolly and Plunkett demonstrated that English speakers aged 2;6, BUT not those aged 2;0, were able to use plural cues to disambiguate referents and to later demonstrate retention of this association. This idea is testable and indeed is one that may be explored in future research. Other studies have shown that children have a tendency to look at displays with more objects (Carey, 1978; Jolly & Plunkett, 2008). Our similar finding here could be due to a bias to look at displays of MORE items.

The visual preference to look more at eight objects instead of one object in the baseline phase of the singular and plural trials has serious implications for understanding our results. This visual bias means that in singular trials they would have to SWITCH their looking in order to respond to the singular cue. In plural trials, children needed only to increase their looking at the plural scene. This effortful switching may explain the lack of an effect in singular trials. Children learning the Spanish plural–singular syntactic system may first learn cues to plural and later learn the relevant cues to singular. For both English- and Spanish-speaking children, the production of plural markers emerges between 1;9 and 3;0.

Early number morphology production has been considered to be a stage of unanalyzed use, showing varying levels of mastery for different cues (Bel, 1988; Marrero & Aguirre, 2003). Understanding how linguistic cues map to the environment is crucial for early language comprehension and may provide a way for bootstrapping and learning words. Research has suggested that learning how plural syntax maps to the perceptual environment may show a trajectory in which children first learn surrounding cues before a full mastery of the noun morpheme alone. The Spanish plural system of simple codas, dominated by one allomorph -s, and with redundant agreement markers, may facilitate early understanding of how plural linguistic cues map to novel referents. These results demonstrate Spanish-speaking children's ability to use plural noun inflectional morphology to infer novel word referents which may have implications for their word learning.

There is a pattern with words with an initial stressed /a/ sound, such as agua ("water"), that makes them seem ambiguous in gender, but they are not. Such words take the masculine article, both definite and indefinite , in the singular form; they also take the singular modifiers algún and ningún when those modifiers precede the nouns. Similar words include el alma / un alma ("soul"), el ala / un ala ("wing"), el águila / un águila ("eagle"), and el hacha / un hacha ("axe"). Still they are feminine and, as such, they take feminine modifiers in both singular and plural forms, and they take feminine articles in the plural form as in las aguas frías. The results do not conclusively indicate that language structure is the only driving force behind the trajectory on which the plural morpheme is acquired, but they are certainly consistent with the hypothesis. The allomorph /-s/ is frequently weakened, aspirated, or lost in many Spanish dialects (Lipski, 1999; Miller & Schmitt, 2010), but the Mexico City dialect always pronounces it (Miller & Schmitt, 2010, 2012).

Thus, our findings converge with Miller's work showing differences in acquisition for children learning different dialects of Spanish with differing levels of regularity in the allomorphs and morpheme presence. Incomplete mastery of the system is also the result of an incomplete mapping of all the appropriate morphosyntactic cues to the MEANING 'more than one'. According to some researchers, children use nominal plural morphology to distinguish 'one' from 'more than one' by 3.5 years of age (Munn, Miller & Schmitt, 2006). Early on, morpheme use may be the result of lexically stored items rather than an understanding of the morphemes and its mapping to conceptual meaning (see Grinstead, Cantú-Sánchez & Flores-Ávalos, 2008; Wagner et al., 2009). The studies presented in this paper are an initial investigation of the linguistic cues that children learning Spanish comprehend as meaning 'more than one'.

In two experiments, we demonstrate that children learning Spanish understand that, in the absence of other social or pragmatic cues, plural syntax refers to sets of 'more than one'. The results have implications for understanding children's mastery of plural morphosyntax mapping to the perceptual environment and provide a basis for a hypothesis for how morphosyntax is acquired. Before presenting the main experiments, we briefly review relevant literature on plural acquisition. Learning the language that maps to these different sets, however, is a piecemeal process. Research also focused on English plural acquisition has suggested that children understand phrases with multiple cues to plurality at earlier ages than noun morphology alone (Kouider, Halberda, Wood & Carey, 2006).

There are a couple of possibilities that may account for such results. One possibility is that children need several cues in order to NOTICE plurality and that this may be true regardless of the language system being learned. Another possibility is that individual plural cues vary in strength, and the observed pattern is due to the varying degrees of comprehension of the different linguistic cues in a phrase. This would mean that children do not necessarily need multiple cues but understand certain of those cues before others (i.e. children may understand verb cues before plural allomorphs). In the present empirical studies we ask two questions.

Second, is the noun morphology cue presented without other cues to number sufficient for this mapping? We tested children aged 2;0 – an age at which, according to previous studies, children are still on the cusp of acquiring plural morphosyntax (Jolly & Plunkett, 2008; Kouider et al., 2006). We tested children in a procedure similar to that used by Kouider et al. in which children's understanding of how language maps to perceptual sets is tested. Experiment 1 tested comprehension of the plural when multiple cues to number are provided.

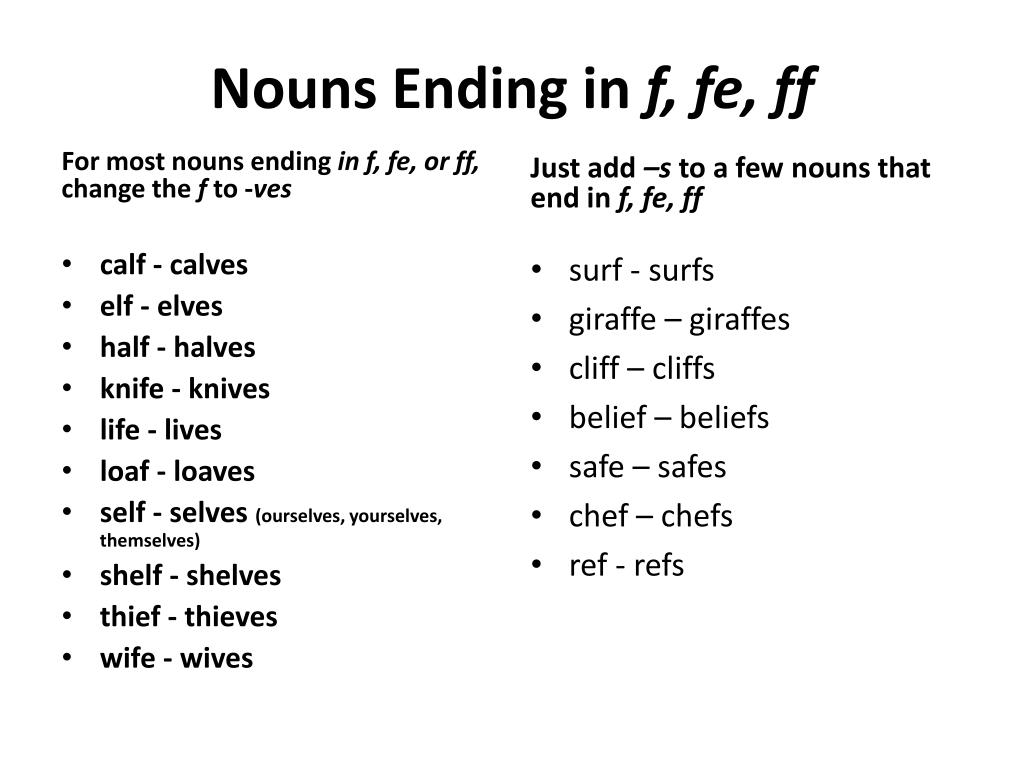

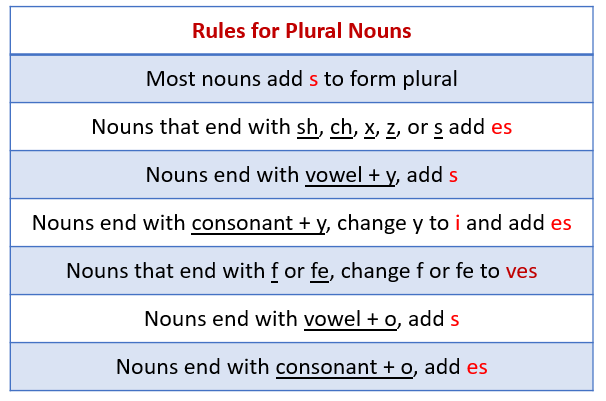

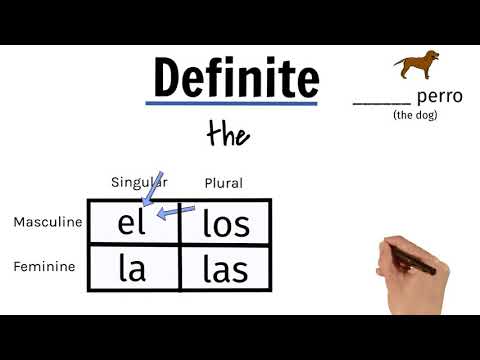

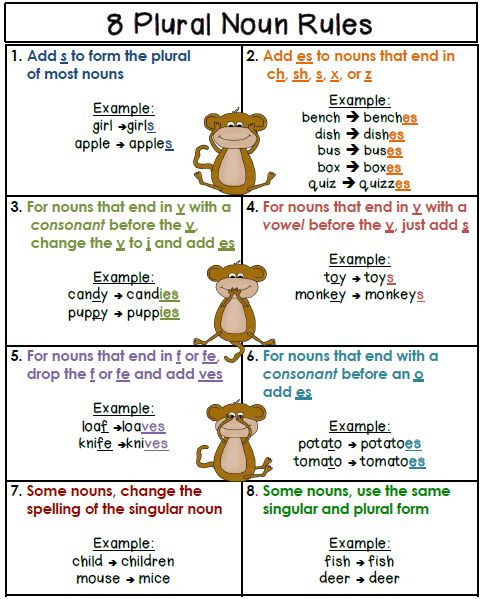

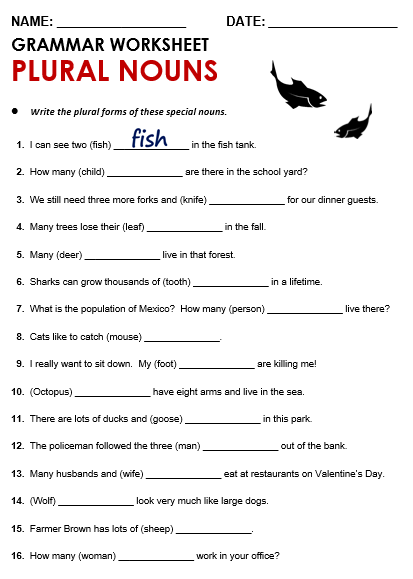

Experiment 2 tested comprehension of noun morphology cues alone. In Spanish, the plural nouns are formed by adding 's' or 'es', also, by adding a definite article 'los' before masculine nouns and 'las' before feminine nouns. Using plural nouns in Spanish is done quite differently than in English. If a noun that ends in "s" or "x" has more than one syllable, and the last syllable is unstressed, its singular and plural forms are the same.

You only need to change the article to plural (el análisis - los análisis, el jueves - los jueves, el tórax - los tórax). The indefinite articles in Spanish areun anduna. These are only used in front of a singular noun. The noun is the word we use to name objects, people, countries, and so on. Like articles, nouns have gender , and number .

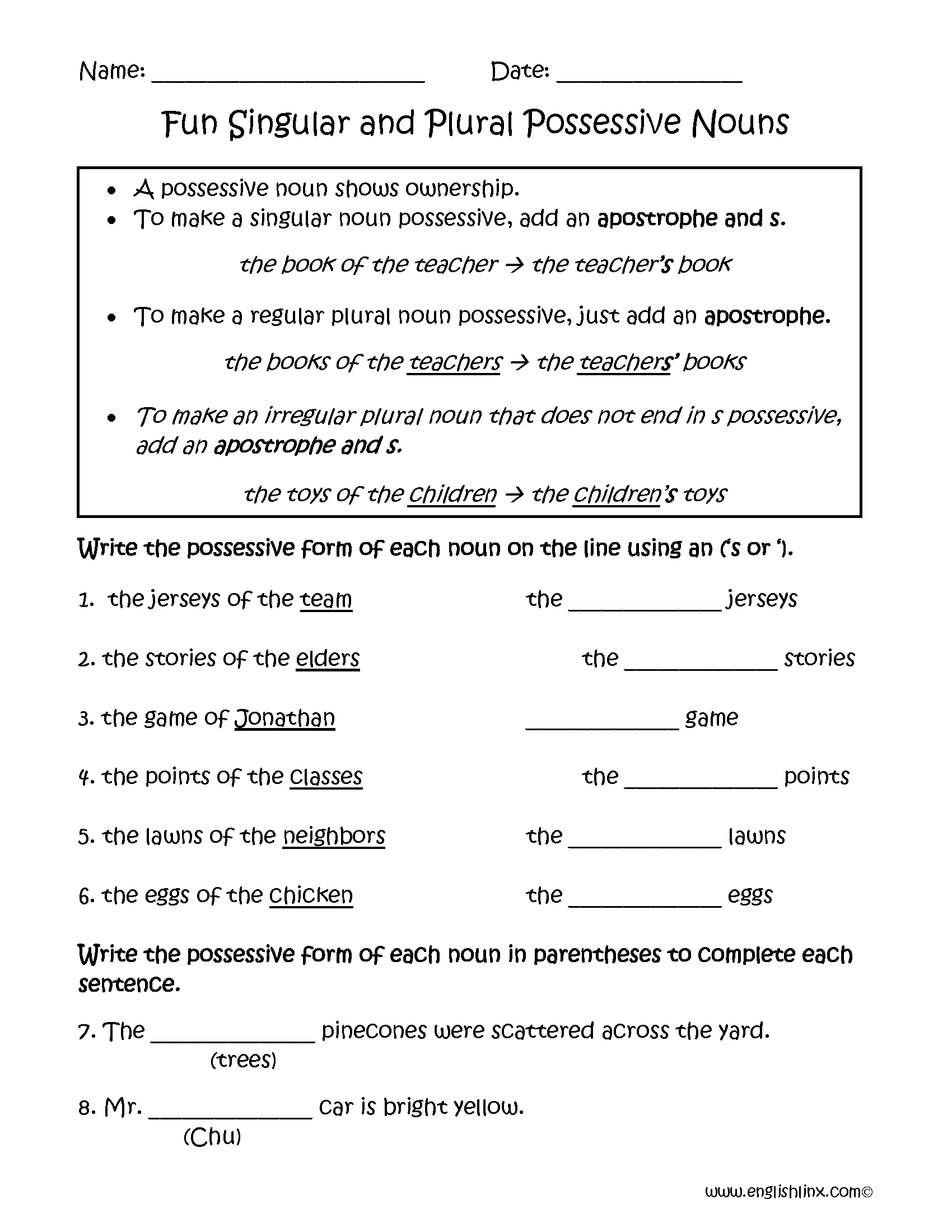

These features must always match the features of the article. In this exercise, we are going to focus on the study and practice of the singular and plural nouns in Spanish. The Spanish plural form is formed by adding an -s or -es to the noun ending. The definite articles which indicate the plural form are los for the masculine and las for the feminine. Note that se is also used for the formal "you" (usted/ustedes). Before you learn how to make a noun plural, however, it's necessary to learn how to pluralize the definite and indefinite articles.

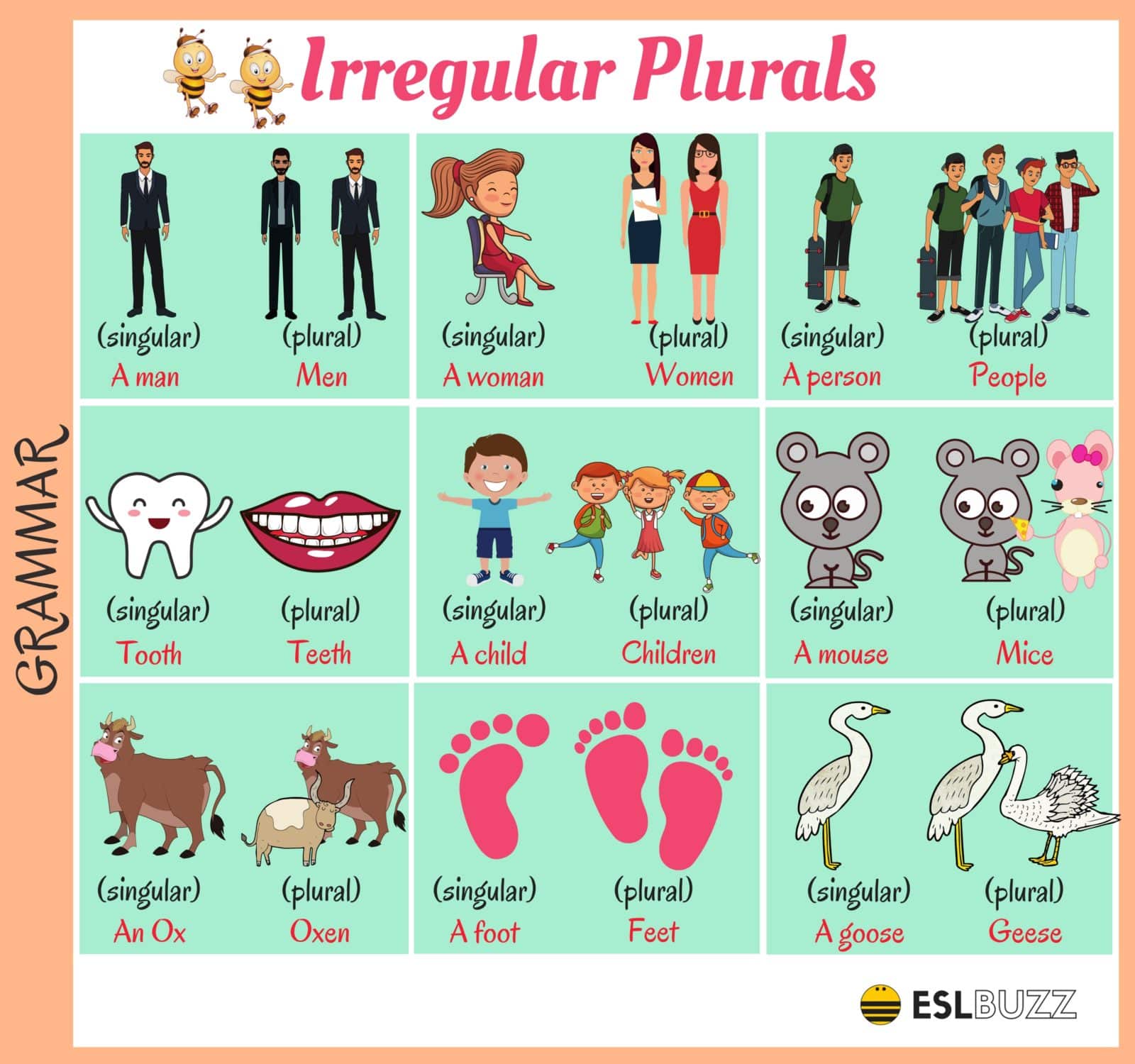

A plural noun will have a plural version of the article in front of it. Comparatively, the definite article in English is the same regardless of whether the noun that follows is singular or plural. In Spanish there are singular nounsandplural nouns, like in other languages. This post is about plurals in Spanish and how to form them, seeing the general rule and also the different cases where there are changes in the spelling of plural nouns. Listed below are many different plural nouns that refer to people, places, and things.

As you read them, think about what singular nouns would be used in their place and if they are regular or irregular plural nouns. Some singular nouns become plural nouns by changing vowels in the middle of the word. There is no rule or pattern that tells you when this happens.

You will just have to learn which words do this as you discover them. A noun that ends in–swill remain the same in its plural form unless there is an accented vowel in front of the–s. If there is an accented vowel in front of the–s, you will add–esand drop the accent to create the plural form. This rule is important to remember with compound nouns because they usually end in–sand usually have the same form for singular and plural.

A word ending in any consonant other thannorswill be stressed on the last syllable. A word that ends in a vowel, ann,or answill be stressed on the next‐to‐last syllable. Because in Spanish the plural form of a word would be stressed on the same syllable as the singular form, it is sometimes necessary to add or remove an accent mark when the plural version adds an entire syllable, such as–es. My name is Jaklien Wotte, I am from The Netherlands. I studied for two weeks at iNMSOL in Granada in septembre 2009, I followed an intensive Spanish course, level A2. I spoke a little bit of Spanish, but I wanted to learn proper Spanish, make sentences, something that I wasn´t able to do yet.

I was also very positive about the flexibility of the school . I followed partly private lessons, what also was a possibility. Granada is of course, beside all of this, a extraordinary beautiful and living city. The school organised activities every night, like a tapas tour, a tour in the Albaícin or a tour to the mountains, Alpujarras, in the weekends. Sometimes the school organised special classnights, were for example the streetlanguage of Andalusia and films were spoken.

My Spanish language progressed a lot, exactly what I wanted. I had a splendid time and I would return to this school for another course. Notice that the singular noun árbol has a graphic accent in the second-to-last syllable . However, when you form the plural, the graphic accent moves to the third-to-last-syllable becoming a proparoxytone word (palabra esdrújula). Similarly, singular nouns like profesor and universidad that are stressed in the last syllable become paroxytone words in the plural form. Which definite article is masculine plural?

The plural of Spanish nouns or "El plural" refers to a basic transformation of words from singular to plural form in order to talk about several objects, instead of a single one. In grammar terms, this property is called NÚMERO GRAMATICALor grammatical number. Consequently, words in the language usually have a singular or plural form , which is easy to determine following some simple rules that we will discuss shortly. In this lesson, we will learn how to make nouns plural in Spanish. The principle is nearly the same as in English.

So it's easy to master plural forms of nouns in Spanish. Here are rules that you need to know if you want to pluralize Spanish nouns. The general rule of plural nouns is that they are created by adding the letter S to the end of a singular noun. For example, you take the singular noun apple and add an S to make the plural noun apples. When comparing singular and plural nouns, we can often say that the plural noun is the "plural of X singular noun." For example, the noun bugs is the plural of the singular noun bug.

For example, the word catsis a plural noun because it refers to more than one animal. On the other hand, the word dog is not a plural noun because it only refers to a single animal. A noun that only refers to one of something is called a singular noun. For the most part, you should be able to identify most plural nouns if you remember that they refer to more than one of something.

Notably, plural nouns cannot follow the articles a and an and always use plural verbs . To help you practice with singular and plural nouns in Spanish we have put together an exercise that we have divided in two parts, the first part is theoretical, to explain how we form the plural in Spanish. What if, on your luckiest day, you won the lottery, would you get yourself a gigantic casa in your favorite place in the whole world or rather purchase dozens of casas , that is, one in each heavenly corner of the planet? Globalization and mass consumption teach us that quantity matters just as much as size does.

We therefore ought to get under our belt that set of rules that enable us to switch and rightly differentiate between singular and plural forms of Spanish words. The first rule for the plural of Spanish nouns says that we add the letter-Sat the end of a word when it ends with a vowel without TILDE such as the words "CASA" and "MESA". Notice that both nouns do not need TILDE and finish in the vowel A. For words ending in "É" like BEBÉ, we still add the letter -Sas this is an exception to the rule. Here are some examples of sentences showing how to make Spanish nouns plural by adding -S.

In this lesson, discover how to make Spanish nouns and their definite articles plural by learning a handful of basic Spanish grammar rules. If the verb requires a preposition (like "talked with" or "jumped on"), the direct object pronoun stays in place; however, it requires a different pronoun in this case. See the section below on prepositional object pronouns for more. Thus, children learning Spanish are exposed in some instances to two plural sounds.

However, voicing assimilation in Spanish is not consistent; it depends on the speaker's speed and stress. In accelerated speech, the voiced is more likely to be produced, when a voiced consonant follows, than in slow speech, as pauses create a scenario resistant to voicing (File-Muriel & Brown, 2011). Many authors agree that assimilation in the voicing of -s is a tendency rather than a mandatory process and acknowledge that its realization is not consistent (Hammond, 2001; Schmidt & Willis, 2011). Thus, voicing assimilation is not categorical but variable.

In Mexican Spanish, and are both considered in comprehension as exactly the same phrase; and are indistinguishable sounds. Thus, despite the occasional use of a voiced , we maintain that Mexican Spanish provides a redundant and regular plural system that should be easily and quickly learned. The plural form of nouns is formed on the basis of its singular form. Thus, when a noun in its singular form ends in a vowel, the plural is formed by adding at the end –s.

The definite articles also change in the plural form. They become "los" and "las." The definite articles will be covered in depth in the next lesson. Count nouns have both singular and plural forms. Today we'll talk about Spanish singular and plural nouns and we'll look at how to make singular nouns plural. (a word with three more syllables that is accented on the third-to-last syllable), the singular and plural forms are the same. When telling someone to do something, add the indirect object pronoun directly to the end of the conjugated verb.

Just as the English pronouns he/she denote gender, Spanish pronouns also need to be changed depending on who you are speaking about. Unlike English, the plural pronouns "we" (nosotros/nosotras), "you all" (vosotros/vosotras), and "they" (ellos/ellas) need to be changed to match the gender of the group. Luckily, pronoun forms are very closely related, so it's usually easy to figure out what they mean when reading or listening to Spanish. On the flip side, one letter or accent mark can completely change the meaning, meaning their relatedness can lead to some difficulty when speaking or writing Spanish.

For example, nominative nouns without the definite article form the plural by adding one of the endings -i, -uri, -e, or -le. For singular nouns that already end in S, we instead add the ending –es. For example, we add –es to the end of the singular noun bus to make the plural noun buses.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.